Get a free story when you subscribe

Lucky 13. That’s how many times I had to submit my novella, Between the Stars I Found Her, before it found a home.

Lucky 13. That’s how many times I had to submit my novella, Between the Stars I Found Her, before it found a home.

At the 2018 Worldcon (San Jose), I attended a mentoring session hosted by the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA). I was paired with Julia Rios, a talented writer/editor who managed Worlds of Possibility. She heard my pitch about two projects I was considering: a second-world fantasy based on ancient Yemen, and a science fiction story set in a socialist paradise that included cloning and personality transfers (i.e., functional immortality).

Julie said I showed more interest in the second idea and encouraged me to pursue it. She was right.

The result was a novella, Between the Stars I Found Her. My POV character is Mylene Vandenberg, whose ex-wife commits suicide. I wanted to explore themes of grief and loss, especially when the concept of true death had become rare.

The story really clicked for me when I put Mylene on a solo journey that takes her far from Earth. She and her ship, The Flying Dutchman, stumble across the corpse of an astronaut lost over a century before. That gave me the opening to play around with several puzzles—who was this person? How did their life pod get into deep space?

The answers could lead Mylene back to Earth. Full circle, as it were.

Easier said than done, certainly. The draft became a story which was rejected several times. I kept at it. My helpful critic group correctly pointed out that the story was too short (and boy were they right), so the story grew into a novella. It was rejected again. And again.

On the thirteenth submission, I found an editor (Mark Bilsborough at Wyldblood) who liked it enough to help me develop Between into a proper novella. Mark had published several of my flash fiction stories and I was happy to work with him again.

The novella’s journey wasn’t an easy one, I’ll be honest. Writing Between the Stars forced me to do research and—Gods forbid—write a real outline rather than simply banging at the keyboard for a few thousand words and call it a draft.

There was also Mundane Reality™ that many writers face: jobs and family and COVID, etc. Somehow, though, it all came together in a shiny wrap-around cover that you can hold in your hand. Imagine that.

In retrospect, I’ve learned a few important lessons. First, my idea for a secondary world fantasy novella/novel wasn’t bad, but I was trying to write something I thought would be popular (Everyone loves epic fantasy, right?) rather than telling a story that meant something to me. Bottom line: listen to your Muse. She knows the score.

Second, you have to back up your Muse with perseverance. And patience. The best stories sometimes take years to find the right editor, the right agent, the right publisher. And even if they do, shit happens. (Buy me a cup of tea and I’ll tell you all about it.)

I’ve often remarked to friends that I hesitate to write longer stories because I’m not willing to let the characters live in my head for at least two years. Well, Mylene lived in my head much longer than that and I still like her a lot.

—

Karl Dandenell is a graduate of Viable Paradise and a Full Member of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Association. He and his family, plus their feline overlords, live on an island near San Francisco famous for its Victorian architecture and low-speed traffic. Karl has published over 50 works of short fiction in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. Follow his occasional posts at Bluesky (@karldandenell.bsky.social) and read more about of his fiction at www.firewombats.com.

Most of my writing career has been spent in long form novels set in the grim and perilous worlds of Warhammer, but I often like to venture beyond that into other forms of writing, genres, and tones for variety and texture. What I mean by that is I need to feel like I’m exercising different writerly muscles when I embark on different projects, whether it’s a novel, a comic, a short story, a screenplay, or whatever. I feel this is good for me and the reader, as it helps keep things new and exciting. It means that when I return to each different genre or project type, I’m enthused to explore it again and not likely to get pigeonholed into one corner. Likewise, as a reader, I like to vary my diet of books between SF, Fantasy, Horror, Crime, Non-Fiction, etc., so I don’t ever get tired of one genre or writer.

Most of my writing career has been spent in long form novels set in the grim and perilous worlds of Warhammer, but I often like to venture beyond that into other forms of writing, genres, and tones for variety and texture. What I mean by that is I need to feel like I’m exercising different writerly muscles when I embark on different projects, whether it’s a novel, a comic, a short story, a screenplay, or whatever. I feel this is good for me and the reader, as it helps keep things new and exciting. It means that when I return to each different genre or project type, I’m enthused to explore it again and not likely to get pigeonholed into one corner. Likewise, as a reader, I like to vary my diet of books between SF, Fantasy, Horror, Crime, Non-Fiction, etc., so I don’t ever get tired of one genre or writer.

The reason I do this with my writing is that each project employs different sensibilities and creative choices, whether it’s the discipline of the word count in a short story, where you want to get in and out of Dodge with speed and clarity, or a novel where you can afford multiple sub-plots and be (a little) more self-indulgent. Then you have screenplays, which have a very definitive structure and format, where all the emphasis is on the dialogue and providing a ‘blueprint’ for the folk who have to shoot what you’ve written. When it comes to comics, I love working with an artist to bring the words on the page to life and leaning on their talents for how to lay out the page. With comics, you also have the fun challenge of pacing the story in such a way that the big reveals, splash pages, and so on all come at the right time on the reader’s page turns.

It’s the same with genre and mythologies, I love to mix and match or slam together wildly different origins to see what comes out. So, you’ll get books like Dead Sky, Black Sun, that fuse a grimdark SF tale with Barker-esque body horror, or A Thousand Sons, that’s a story of space wizards in a gothic tragedy of hubris.

That variety is what I had in mind when I first started developing the ideas for Wolves of Winter. I wanted to write an epic story of Viking warriors that ventured into magical and supernatural territory, which combined my love of various mythologies. As much as I love Roman, Greek, and Egyptian mythologies, I didn’t feel they were the right fit, and given that as a kid in Scotland, I’d grown up on stories of Celtic mythology, with its Kelpies, Selkies, and the Tuath Dé Danann, that seemed entirely appropriate a mash-up. Bringing the grand mythologies of the Norse and the Celts together allowed me to delve into both cultures in a way that felt real and authentic (and, most importantly, exciting!).

It’s my hope that, so long as I stay enthused for my craft by allowing for that blending of story types and genres I can keep entertaining my readers in exciting and unexpected ways for many years to come.

—

Graham McNeill is a Scottish, LA-based, award-winning, New York Times best-selling author, screenwriter, and games developer. Over the years, Graham has written for numerous global franchises, working on Riot’s League of Legends and on their Emmy-Award-winning Netflix show, Arcane; Games Workshop’s Warhammer and Horus Heresy settings; Blizzard Entertainment’s Starcraft universe, and the Dark Waters trilogy for Fantasy Flight Games Arkham Horror range. To date, Graham has penned forty-five novels, ninety-plus short stories, audio dramas, and comics. His novel, Empire, won the David Gemmell Legend Award for Best Fantasy Novel in 2010, and four of his novels in the Horus Heresy series have gone on to become New York Times best-sellers.

You’ve all heard it said: Two great tastes that taste great together. Peanut butter and chocolate. Yum. I tend to look upon writing fiction in the same way I look at my snack options. I love mixing genres. Blending genres into something unique thrills the creator in me and I think my characters enjoy it too.

You’ve all heard it said: Two great tastes that taste great together. Peanut butter and chocolate. Yum. I tend to look upon writing fiction in the same way I look at my snack options. I love mixing genres. Blending genres into something unique thrills the creator in me and I think my characters enjoy it too.

I write thrillers often. The beauty of this is that thrillers pair well with almost anything. Action/thriller. Check. Crime/Thriller. Yep. SciFi/Thriller. Uh huh. You get the idea. If you look at any of my thrillers, there is definitely a blending of multiple genres. It even boils down to the way I pitch titles to potential readers. For example, the pitch for Evil Ways, my first novel that was released in 2005, is “Imagine if Die Hard’s John MacClane found himself in an 80’s slasher movie.” It also works outside of thrillers. Horror also pairs well with others. I write a horror/western series, for example. In my Dante series, it’s “Imagine if Deadwood also had monsters.”

This blending of two different, but recognizable, ideas let readers know what they are in store for before they open to the first page.

How do writers know when blending genres works? That’s a tough question to answer because all writers are different and our unique voice helps us determine how scenarios play out. If I am writing a mystery, for example, there are different types. A cozy mystery has no, or very little, elements of danger. The odds of your main character getting hurt, killed, or even severely startled is infinitesimal. Mixing in a thriller component changes the dynamic because thrillers inherently come with an element of danger, of thrills. It’s right there in the description. Characters aren’t always safe in a thriller.

Even if a cozy mystery and mystery/thriller use the same plot, you will get two different stories because of the thriller element added. Thriller adds a sense of danger to stories and, as a writer and reader, that appeals to me. I recently co-wrote a cozy mystery with a friend and it was a bit of a struggle to not add in thriller elements as I normally would when writing a novel. I use thriller elements to enhance the story. A lighthearted story gets a bit of bad news that gives the characters a problem to overcome. In a mystery, thriller elements can knock a character down and then help them grow by how they rally and get back up. Thriller elements are usually impediments to the status quo. How your characters respond to these elements adds weight to the story and the characters themselves. Do they learn something from this element? Do they grow? Do they buckle under the pressure? Thriller elements allow me, as a writer, to test my characters. The best of them come away from these stories stronger thanks to the adversity they faced.

For me, writing always starts with character. Not every character is the right fit for every story. Certain characters are perfect fits for a thriller while others are not. Also, thrillers can be funny, romantic, and even heartfelt, each with an element of danger. That’s one of the reasons I like using the genre as a mixer. I encourage everyone to experiment with blending genres. You might discover something interesting in the process.

—

Bobby Nash is an award-winning author, artist, and occasional actor. He writes novels, comic books & graphic novels, novellas, short stories, audio scripts, screenplays, and more. Bobby is a member of the International Association of Media Tie-in Writers, International Thriller Writers, Southeastern Writers Association, and Atlanta Writers Club. From time to time, he appears in movies and TV shows, usually standing behind your favorite actor. Sometimes they let him speak. Scary, we know. For more information, please visit Bobby at www.bobbynash.com, www.ben-books.com, and across social media.

All four Dante ebooks are currently $0.99 for a limited time.

I love writing short story horror because the swing of ideas can be boundless even within a single book. You can be transported from modern settings to my favorite: Gothic backdrops. There is something spectacularly spooky about old weather-worn, eerie mansions, houses, and the time period itself. The creak of floorboards, the chill in the air, the distant tolling of a bell—those are the sounds echoing in your mind long after the last page is turned. These decaying structures hold secrets in every shadowed corner, and it’s easy to imagine their walls remembering every scream, whisper, or tragedy that’s ever unfolded within.

I love writing short story horror because the swing of ideas can be boundless even within a single book. You can be transported from modern settings to my favorite: Gothic backdrops. There is something spectacularly spooky about old weather-worn, eerie mansions, houses, and the time period itself. The creak of floorboards, the chill in the air, the distant tolling of a bell—those are the sounds echoing in your mind long after the last page is turned. These decaying structures hold secrets in every shadowed corner, and it’s easy to imagine their walls remembering every scream, whisper, or tragedy that’s ever unfolded within.

What fascinates me most is the way horror allows you to explore deep-rooted fears through different lenses. One moment, you are in a suburban neighborhood where things seem normal, until they go wrong. The next, you are wandering through fog-choked moors toward a crumbling estate that feels alive. The flexibility of short horror fiction means you do not need hundreds of pages to unsettle someone; a single well-placed sentence, a twist of imagery, or the slow reveal of something deeply wrong can do the trick. That brevity forces you to be sharp, precise, and atmospheric—every word counts, and every detail needs to serve the chill.

To me, the Gothic setting in particular is ripe with symbolism. The decay of the building often mirrors the decay of the soul or mind. Rain lashes the windows like ghostly fingers trying to get in. Candles flicker in halls where no wind should reach. These are the environments where shadows do not behave quite right, where time feels slowed or twisted. I love tapping into the classic themes of madness, isolation, fear of the dark, haunted objects, etc.—but presenting them in new ways that still honor the roots of the genre.

Writing these stories also feels like being in conversation with the greats—Poe, Lovecraft, Shirley Jackson. (I take great pride in mimicking the Gothic period language for many of my stories.)

Each one of the greats brought their own flavor to horror, and I strive to do the same. Whether it is a haunted diary, a malevolent mirror, or something unspeakable lurking beneath the floorboards, I want to leave readers with that lingering feeling of unease. The kind that stays with you in the quiet moments. The kind that makes you hesitate before turning off the light.

Ultimately, I think short form horror reminds us, in a snapshot version, of the unknown all around us. It plays with our sense of safety and dares us to look closer. And I cannot get enough of it.

—

Mark K. McClain is a multi-award-winning author who discovered his love of writing as a pre-teen, inspired by the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, David Eddings, Isaac Asimov, Robert Jordan, Agatha Christie, Stephen King, and many others. His 20-year military career carried him around the globe, experiences that enriched his worldbuilding and grounded his stories in realism.

Beyond fiction, he has published a wide range of outdoor-themed and human-interest articles, from local history features and parenting columns to international pieces written in China and Uganda. He writes fantasy, science fiction, and Gothic horror—and sharing the magic of storytelling remains one of his greatest joys.

Mark makes his home on an island off the coast of Washington State with his life partner, Rochelle, and their beloved furry companions.

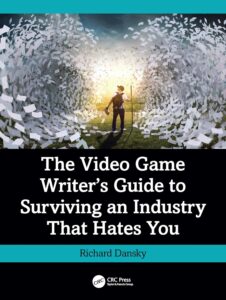

I have been writing video games for over a quarter of a century, which, in hindsight, is kind of terrifying. I have seen games go from teams of a dozen being “maybe too big” to working on teams with a thousand developers spread out across a half-dozen countries and an equal number of time zones. I have gone from writing wall-of-text mission briefings because we couldn’t put dialog in the actual gameplay to games where we literally had to write well over a hundred thousand lines of just systemic dialog, never mind the stuff related to the plot and the characters. I have seen game writing grow from a last-minute “oh, the designer will do it in their spare time” afterthought to a distinct role. And I have seen nonsense the likes of which you would not believe, and which I ultimately decided maybe somebody should say something about, to keep it from happening again (and again and again).

I have been writing video games for over a quarter of a century, which, in hindsight, is kind of terrifying. I have seen games go from teams of a dozen being “maybe too big” to working on teams with a thousand developers spread out across a half-dozen countries and an equal number of time zones. I have gone from writing wall-of-text mission briefings because we couldn’t put dialog in the actual gameplay to games where we literally had to write well over a hundred thousand lines of just systemic dialog, never mind the stuff related to the plot and the characters. I have seen game writing grow from a last-minute “oh, the designer will do it in their spare time” afterthought to a distinct role. And I have seen nonsense the likes of which you would not believe, and which I ultimately decided maybe somebody should say something about, to keep it from happening again (and again and again).

The thing I realized is that while there is a ton of advice out there on how to do the actual writing for video games—and don’t get me started on how writing for video games is very, very different than writing for anything else, or we’ll be stuck on that all day—but there was pretty much nothing on how to do the day to day job of being a game writer. There were no classes, there was no formal training, there was no core body of institutional knowledge, and since every studio treated their writers and their writing process differently, that meant that there was no way to learn how to actually function and survive in the role except by marching boldly into a field of rakes and stepping on every single one. Plus, if you changed jobs, you had an all-new set of rakes to play with.

Also, it occurred to me, that if all us game writer types had a playbook to work from, we could then start pushing for good practices from our end. We could explain why game writing needed time in the schedule for iteration and polish, and how to give useful feedback, and all that good stuff that would hopefully prevent some of those age-old mistakes from getting made over and over and over. We could actually make game writing better.

Here’s the thing: Game writing has very much become my calling. When I first stumbled into video games in 1999, I had no idea that it was going to be my life’s work. But somewhere along the way, that’s what happened. I’ve seen the craft germinate and grow and evolve. I’ve been there for the foundation of the first professional organization for game writers, and I’ve done my best to nurture the community and students who are looking to be the next generation. I don’t want my name on anything; I want this form that has defined my professional life to keep improving, and to do anything I can to help create a craft that the next cohort of game writers can pick up and do things I never dreamed of with.

That is why I sat down to write this text book (The Video Game Writer’s Guide To Surviving an Industry That Hates You). I jokingly tell people it took me 25 years to write but six months to type. It’s a joke, but there’s some truth there. This is my thank you to the craft, and to the people who helped me along the way, and maybe a toolkit for those coming after me.

—

The author of 8 novels and 2 short story collections, Richard Dansky is widely regarded as a leading expert on video game narrative and writing. He has written for franchises including The Division, Assassins Creed, Far Cry, Splinter Cell, and many others, and was also a key contributor to White Wolf’s classic World of Darkness horror RPG setting. His upcoming projects include the novel Nightmare Logic from Falstaff Dread, the graphic novel Bridgewater from Delcourt, and the nonfiction book The Video Game Writer’s Guide To Surviving an Industry That Hates You. He also likes scotch.

Everyone is a philosopher; this is a core sentiment of mine. Some are certainly more formal and exploratory in their reflection, but we all meet with life’s great abstractions, and we all carry doubt and curiosity. Most of us will, in one way or another, attempt to pin some logic to our grief, purpose to our existence, shape to our sense of self.

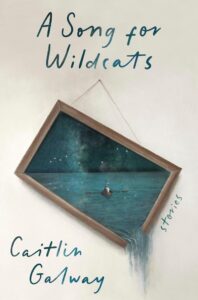

The characters in my collection, A Song for Wildcats, pull such introspection to the forefront of their experiences. Each story explores some form of grief, trauma, and intimacy while spanning distinctly different settings, from an Irish peninsula at the height of the Troubles, to the Corsican seafront during the 1968 student revolts. But they also squint through a metaphysical lens, and my characters (like myself) often find themselves fixated on unanswerable questions: What defines love and violence? How far back should blame extend? What’s the essence of self, especially if self is fluid, and how does one hold onto it?

“The Lyrebird’s Bell,” for example, follows the friendship between two young girls in the isolated bush of 1940s Australia. Facing a severe, lonely homelife, each girl crafts stories, often unsettling and fantastic ones, that are somehow more rational and less painful than the truth. As one girl is consumed by these fantasies, the other grows desperate to remain grounded in reality. In doing so, she begins to question what constitutes reality—and as no one person’s reality is definitive, whose versions are worthier, or more valid?

As I wrote the collection, I rediscovered a love of philosophy, particularly the works of Plato. (Even the title A Song for Wildcats is a little wink to Homer’s Iliad—due to what we’ll call an “enthusiasm” for ancient humanism.) It became an obsession—a healthy obsession, I would argue—which drove me to make dramatic shifts in my life. I gradually began to reconfigure my relationship with human interaction, identity, and the world around me—all of which led me wandering quietly through mountains, sitting alone in faraway villages, and more deliberately layering my work with metaphysical questions to which I’ve long been intuitively drawn. If grief does not leave us, when does it become wisdom? Why does suffering lead toward deeper empathy for some, and for others, a desire to harm?

However, I did not want to write a textbook, nor would I condescend to readers by assuming they required easy explanations. Instead, my hope was to offer stories in which the various layers—such as narrative, emotional, symbolic, and philosophical—connect patiently and meaningfully, so that one does not need to research ancient Greek philosophy, or Irish folklore, or twentieth-century existentialism, in order to be impacted by them. My characters are driven by a desire for connection and clarity, and it was important to me that the philosophical lens amplify each story’s heart, not clog it. These stories are my effort to capture, in my own small way, the peculiar human habit of stumbling, unwittingly, into transformation.

—

Caitlin Galway’s short story collection A Song for Wildcats has been featured as a must-read by the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star, and named an Indigo Best Book of 2025. Her debut novel Bonavere Howl was a spring pick by the Globe and Mail, and her work has appeared in journals and anthologies across Canada, including Best Canadian Stories, EVENT, and Gloria Vanderbilt’s Carter V. Cooper Anthology, and on CBC Books.

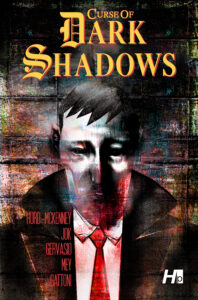

During the pandemic, I was in a comics writing group. I was convinced we’d all be dead and there would be no more conventions. Conversations turned, as they inevitably do, to the franchises we’d love to take a crack at. I have always encouraged creators to focus on their own ideas more so than other IP, so I dreaded the conversation getting to my turn. And when it did, I began to answer (shocking myself even): it was Dark Shadows.

You see, I’d also been rewatching Dark Shadows (the entire 1225 episode catalogue) during the pandemic. If it was all going to be over, what better family to go out with than the Collins family of Collinsport, Maine? So as I began to answer the IP question, the idea for the story sprang, fully formed, into my mind. That very rarely happens for me as a writer.

No spoilers here, but thematically, inspiration can be found in WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE by Shirley Jackson.

There’s Truman Capote and Harper Lee and William Faulkner all in there, too, but all good Dark Shadows storylines were based on some classic fiction. So my approach would be Southern Gothic, channeling my own lived experience and my fractured family ties into a story about the Collins family. Why Southern Gothic? It’s hallmarks: dilapidated mansions, deeply flawed humans usually entrapped in a generations-long family feud, and the sinister events which arise from all of the above. If you know Dark Shadows, then you can see the connections.

I do feel connected to Dark Shadows. My mother would race home from school to watch when the show was originally airing. I haven’t spoken to her in almost 15 years, thus this project was an incredibly healing one. I found the resolution I won’t find in this life. I’m at peace with that. We never discussed Dark Shadows when I was a child. I knew she liked it. While we shared a love of the show, what could have perhaps made us closer never did. But in watching the show in its entirety, I felt that I was able to make a relationship with it (the show) separate from her, and also resolve some of our conflict for myself in writing this new chapter of the show.

So here we are, almost three years later from the comics Discord discussion, and the book is coming out soon. There’s a short and sweet story behind my entrance into the officially licensed world of Dark Shadows, but I’ll save that one for another dark and stormy night.

—

Craig Hurd-McKenney is a Xeric grant recipient and Ignatz-nominated comic book writer living in Seattle, WA. He has been making comics since 2000. For more information about Craig, please visit: https://www.hspcomix.com/

Answering the question of WHY DO I WRITE? (something I encourage all writers to do), I have concluded that my WHY is this: I write to tell stories about underrepresented people and underrepresented places in a way that is accessible, and hopefully, entertaining.

Answering the question of WHY DO I WRITE? (something I encourage all writers to do), I have concluded that my WHY is this: I write to tell stories about underrepresented people and underrepresented places in a way that is accessible, and hopefully, entertaining.

The underrepresented place I most often write about is Saskatchewan, my home province. The underrepresented people I most often write about are members of the LGBTQ+ community. The combination of the two is, I feel, truly underrepresented and rarely found in Canadian mystery genre material.

As a writer writing about LGBTQ+ characters, I have on occasion encountered people, usually interviewers or reviewers understandably looking for an angle, decide that I am the spokesperson for that community. They are mistaken. I am one person, one voice. Deciding I am the spokesperson for the LGBTQ+ community is like a Martian, freshly landed on earth, deciding I am the spokesperson for all humans.

That being said, as a mystery writer who is a member of, and advocate for, the LGBTQ+ community, my hope is that my singular voice, my presence and representation in the publishing industry, encourages more voices to speak out and helps to move the community out of the category of being underrepresented.

Even so, I have found you cannot please everyone, outside or even inside your own community.

I was fortunate to find a publisher for my first book without agent representation. I was about 4-5 books into my first mystery series when I received a letter from a graduate student completing his Master’s thesis at Carleton University. I was quite surprised—and I must admit, rather flattered—to learn that the subject of his thesis was my Russell Quant series.

He sent me a copy of the abstract which, in part, read…now, keep in mind the series has a main character who is gay:

“With Russell Quant, Bidulka has shifted the originally well-defined, straight-forward, stolidly masculine identity of the hard boiled, urban crime-fighting hero to a marginal landscape, where subversion, introspection, and humour reign.

“In this paper, I contend that Bidulka’s writing queers not only for the detective fiction genre, but also the regional landscape that his imagined communities inhabit, and myths of Canadian nationhood that bind them.”

Making no claim of being a great academic or literary scholar, I readily admit I didn’t really understand most of the abstract’s claims—but it sounded pretty good.

Some months later, this same grad student sent me a copy of his now published thesis. Once again, this was a high-minded, rather lengthy, scholarly document, but I was smart enough to recognize that in slow methodical fashion this student had deconstructed every book in the series and then completely tore them to shreds for:

“carelessly giving voice to the “homonormalization of the entire lesbian and gay community in Canada today.”

So, yup, if you were wondering, that was me. I did that to the entire LGBTQ+ community in Canada.

Lesson learned. You can’t please everyone all of the time. But—and here’s where light comes from dark—about a year later, this same graduate student was delivering his paper at a conference in California. In the audience that day was another gentleman who, for some inexplicable reason, after hearing the same conclusion noted above, felt compelled to read my books. And today, that gentleman is my literary agent.

—

Anthony Bidulka’s books have been shortlisted for Crime Writers of Canada Awards of Excellence, Saskatchewan Book Awards, a ReLit award, and Lambda Literary Awards. Flight of Aquavit was awarded the Lambda Literary Award for Best Men’s Mystery, making Bidulka the first Canadian to win in that category. In 2023, in addition to being shortlisted for a Saskatchewan Book Award and Alberta Book Publishing Award, Going to Beautiful won an Independent Publisher Book Award being named Gold Medalist as the 2023 Canada West Best Overall Fiction novel and was awarded the Crime Writers of Canada Award of Excellence as Canada’s Best Crime Novel for 2023. https://anthonybidulka.com/

Mourning a Life that Never Was

Mourning a Life that Never Was

When we’re young, we believe we have complete control over our lives. Everything we dream of achieving will happen, if for no other reason than we want it. We’re told good people are rewarded, so as long as we’re good, we’ll get the life we deserve.

But that isn’t how the universe works. At the age of nine, I decided I was going to be a ballet dancer. But after fifteen years of lessons, I finally had to accept that I had neither the talent nor the body required to dance professionally.

Years later, I was introduced to the concept of grieving non-events, also called non-finite grief, the grieving of things desired but never achieved. My disappointment and resentment now had a name.

It’s hard to accept that we’ve been denied the life we so desperately want. Valentine’s Day and Mother’s and Father’s Days come around every year to remind us that we are alone and/or childless, and how unfair it is that everyone else seems to be celebrating what we can’t.

While friends and family might be inclined to tell us to buck up and get over it, it’s not that simple. We have to go through a grieving process as painful as the loss of a loved one, because we have lost a loved one. We’ve lost that part of ourselves that was going to be a parent or homeowner, marine biologist or dancer.

In A Dark Death, the second book in my Meredith Island Mystery series, my amateur sleuth, Kate Galway, shares with her best friend her dream of becoming a university professor. “I had a whole different life planned out for myself. I was going to get my doctorate and teach English to people who not only knew George Eliot was a woman, but had read all her books and could discuss them with some reasonable degree of insight.” But while finishing her Master’s degree, Kate became pregnant. When her daughter was born, she gave up her graduate studies and taught high school to help support her family. Not becoming a university professor is Kate’s non-event.

Instead of moving on, Kate has held onto her grief for almost thirty years. In her mind, she settled for a career which is second-best, and therefore she is second-best. Those who can’t do, teach, and those who can’t teach university, teach spotty, moody adolescents, she believes.

When she meets a visiting archaeology professor, Kate learns about the often ruthless competition and politics of the job. “It isn’t all Jane Austen conferences, believe me,” she is cautioned. Later, her friend tells her that there is no guarantee she would have been happy teaching university, and that she could just as easily have spent her life wishing she’d taken a high school job instead. It’s then that Kate realizes that the perfect life she envisioned is a fantasy, and she can begin to heal.

How do people grieve their lost selves? “Grieving the Life You Expected: Non-finite Grief and Loss,” posted on the What’s Your Grief website, lists some actions you can take. These are my favourites. I hope they help.

—

Alice Fitzpatrick has contributed various short stories to literary magazines and anthologies and has recently retired from teaching in order to devote herself to writing full-time. She is a fearless champion of singing, cats, all things Welsh, and the Oxford comma. Her summers spent with her Welsh family in Pembrokeshire inspired the creation of Meredith Island. The traditional mystery appeals to her keen interest in psychology as she is intrigued by what makes seemingly ordinary people commit murder. Alice lives in Toronto but dreams of a cottage on the Welsh coast. To learn more about Alice and her writing, please visit her website at www.alicefitzpatrick.com.

Why I was Afraid to Engage with the News

Why I was Afraid to Engage with the News

Sometimes I worry that reading the news is above my paygrade, or that I’m being pushed to believe that it is.

Here’s an example: I was reading articles about Trump’s invasion rhetoric, then was surprised when it suddenly stopped. Our then provisional, now permanent PM called him, reporters said. Whatever happened in that phone call convinced him to lay off the 51st state threats, they said. Carney was a banker. He understands financial levers. He probably threatened something to do with bonds. That makes sense, I said in subsequent conversations with friends, although it didn’t really make sense to me. I’ll level with you. I don’t know that much about bonds. I certainly don’t know anything about global financial levers. I started by looking up the terms. The AI loaded without my consent on all my devices chimed in, offering to help, to explain, to summarize the hard stuff for me.

I’m concerned about environmental costs of AI. I’m worried about errors and hallucinations, too. But, I have to admit, I was so overwhelmed that I considered taking it up on its offer. But then I paused.

Reading is more involved than just unlocking words. Reading comprehension, real understanding, means figuring out context too. Reading well requires deep dives.

How I Almost Ruined Reading Ten Years Ago

Let’s rewind a decade. When my son was little, I worked at night so that I could be with him during the day.

The days themselves were joyful, fun, frenetic and fast moving. We went to park to class to park together, and as we walked from place to place, he pointed at signs and asked me to read them to him. I loved those times because they gave me a bit of a breather too. He pointed, I read out mechanically, and I let my thoughts wander. Eventually, he started pointing and telling me what was written on all the signs. I remember looking down at him in wonder: he’d memorized some but was audibly sounding out others. It became clear that he was teaching himself to read this way.

Cool, I thought. I then consulted parenting books just to make sure. Not cool, said the manuals. Parents shouldn’t teach reading haphazardly, or they run the risk of confusing their kids. They should have a plan. OK, I thought. I could do that.

The books themselves didn’t agree with what I was doing, but they didn’t agree with each other either, so formulating a plan was rough. Kids should learn to read by being presented with books, said some, like some kind of literary osmosis. Kids should learn by sounding out words. Kids should learn with phonics, or flash cards, or diphones. I went out and tried it all. My child is a sweetheart and put up with all of it, all the while still asking me questions and teaching himself to read on his own, in his own time, thank goodness.

The one thing all the parenting books did agree on was that I shouldn’t just teach decoding words, that I should teach him to read to understand context and subtext and to read between the lines as well. That required background information. That was advice that I could get behind, and not only because it seemed harder to make a mess out of than reading itself.

The books’ advice, everyone’s advice, was to read as much as you could to your child, as widely as you could, and present as much material as possible. Dive into as many subjects as you can. Dive often, and dive deep. That’s the guidance that I remember most from that period.

I also recognized that it was advice that was relevant to my own life. When I read the news, I remembered, I often worried that I was missing stuff. The more info you have, the books all pointed out, the more you can read between the lines. Be sure to fill yourselves with information. This, I realized, meant me too.

How I Live the Deep Dive Method

Luckily, my child has loved this strategy. He’s a deep diver by nature. He’s one of the completist kids for whom “collect them all” makes sense and becomes a fun and hilarious life mission.

Plays, books and TV shows have become fun entry points. We saw The Three Sisters by Inua Ellams, a phenomenal adaptation of The Three Sisters set in Nigeria during the Biafran War, and we took deep dives into Nigerian history. My son read Time Atlas by Robert Hegarty and History as It Happened: A Map by Map Guide published by DK. His parents are reading The Fortunes of Africa by Martin Meredith and How Europe Underdeveloped Africa by Walter Rooney. We watched Young Sheldon and have been reading entries into the world of Physics like The Elegant Universe by Brian Green and Astrophysics for Young People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson. Sometimes questions inspire other questions, and sometimes missions just materialize. We’ve been reading about code breaking during the second world war, the history of video game consoles, the history of US elections, the history of all of soccer, and all histories and timelines of all Zelda games, to name a few deep dives.

My son lets experiences inspire him, and, when he has a question, he works to answer it completely. I’m so inspired by that. I’m trying to live that way too.

I took a deep dive into the Chernobyl nuclear accident, and that inspired a whole novel. I’ve read a ton about the Covid epidemic and climate change and children’s development, and those deep dives are inspiring the next one. I’m trying to do it more often. I’m trying to do it more widely. When I have a question, I try to find a way to dive deep.

Deep Dive with Me

I’m still fighting through the news. I want to understand this situation that we’re all in, and I’m not going to ask an AI copilot to do it for me.

So even though it scares me, I’m learning about economics. I’m reading The Ascent of Money by Niall Ferguson and Dr. Strangelove’s Game by Paul Strathern. Those books have led to other questions, so I’m also reading about the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the life of Ignaz Semmelweis, the history of asbestos, etc. I’m also reading about the French Revolution. Maybe I’m going back too far. Maybe I’m filling gaps that I shouldn’t have had before. I’ll level with you again. There are gaps in my knowledge, and I’m afraid they might be nig ones.

I’m going on more deep dives besides. I’m getting in on dives with friends. I have a friend interested in music, so I’m reading The World in Six Songs and I Heard There was a Secret Chord by Daniel Levitin.

I’m enjoying the process. I’m getting in on friends’ deep dives. I’m giving myself the confidence that even if I’m doing it imperfectly, even if I don’t understand every little thing, I’m engaging in the news and world events, and I’m protecting my organic intelligence.

—

Alexis von Konigslow is the author of The Capacity for Infinite Happiness. She has degrees in mathematical physics from Queen’s University and creative writing from the University of Guelph. She lives in Toronto with her family.

Jennifer Brozek is a multi-talented, award-winning author, editor, and media tie-in writer. She is the author of Never Let Me Sleep and The Last Days of Salton Academy, both of which were nominated for the Bram Stoker Award. Her YA tie-in novels, BattleTech: The Nellus Academy Incident and Shadowrun: Auditions, have both won Scribe Awards. Her editing work has earned her nominations for the British Fantasy Award, the Bram Stoker Award, and multiple Hugo Awards. She won the Australian Shadows Award for the Grants Pass anthology, co-edited with Amanda Pillar. Jennifer’s short form work has appeared in Apex Publications, Uncanny Magazine, Daily Science Fiction, and in anthologies set in the worlds of Valdemar, Shadowrun, V-Wars, Masters of Orion, Well World, and Predator.

Jennifer has been a full-time freelance author and editor for over seventeen years, and she has never been happier. She keeps a tight schedule on her writing and editing projects and somehow manages to find time to teach writing classes and volunteer for several professional writing organizations such as SFWA, HWA, and IAMTW. She shares her husband, Jeff, with several cats and often uses him as a sounding board for her story ideas. Visit Jennifer’s worlds at jenniferbrozek.com or her social media accounts on LinkTree.