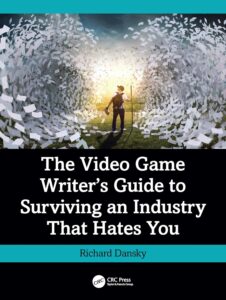

Today, Richard Dansky tells me why it took him 25 years to create a textbook on what it is like to write as a career for the videogame industry.

I have been writing video games for over a quarter of a century, which, in hindsight, is kind of terrifying. I have seen games go from teams of a dozen being “maybe too big” to working on teams with a thousand developers spread out across a half-dozen countries and an equal number of time zones. I have gone from writing wall-of-text mission briefings because we couldn’t put dialog in the actual gameplay to games where we literally had to write well over a hundred thousand lines of just systemic dialog, never mind the stuff related to the plot and the characters. I have seen game writing grow from a last-minute “oh, the designer will do it in their spare time” afterthought to a distinct role. And I have seen nonsense the likes of which you would not believe, and which I ultimately decided maybe somebody should say something about, to keep it from happening again (and again and again).

I have been writing video games for over a quarter of a century, which, in hindsight, is kind of terrifying. I have seen games go from teams of a dozen being “maybe too big” to working on teams with a thousand developers spread out across a half-dozen countries and an equal number of time zones. I have gone from writing wall-of-text mission briefings because we couldn’t put dialog in the actual gameplay to games where we literally had to write well over a hundred thousand lines of just systemic dialog, never mind the stuff related to the plot and the characters. I have seen game writing grow from a last-minute “oh, the designer will do it in their spare time” afterthought to a distinct role. And I have seen nonsense the likes of which you would not believe, and which I ultimately decided maybe somebody should say something about, to keep it from happening again (and again and again).

The thing I realized is that while there is a ton of advice out there on how to do the actual writing for video games—and don’t get me started on how writing for video games is very, very different than writing for anything else, or we’ll be stuck on that all day—but there was pretty much nothing on how to do the day to day job of being a game writer. There were no classes, there was no formal training, there was no core body of institutional knowledge, and since every studio treated their writers and their writing process differently, that meant that there was no way to learn how to actually function and survive in the role except by marching boldly into a field of rakes and stepping on every single one. Plus, if you changed jobs, you had an all-new set of rakes to play with.

Also, it occurred to me, that if all us game writer types had a playbook to work from, we could then start pushing for good practices from our end. We could explain why game writing needed time in the schedule for iteration and polish, and how to give useful feedback, and all that good stuff that would hopefully prevent some of those age-old mistakes from getting made over and over and over. We could actually make game writing better.

Here’s the thing: Game writing has very much become my calling. When I first stumbled into video games in 1999, I had no idea that it was going to be my life’s work. But somewhere along the way, that’s what happened. I’ve seen the craft germinate and grow and evolve. I’ve been there for the foundation of the first professional organization for game writers, and I’ve done my best to nurture the community and students who are looking to be the next generation. I don’t want my name on anything; I want this form that has defined my professional life to keep improving, and to do anything I can to help create a craft that the next cohort of game writers can pick up and do things I never dreamed of with.

That is why I sat down to write this text book (The Video Game Writer’s Guide To Surviving an Industry That Hates You). I jokingly tell people it took me 25 years to write but six months to type. It’s a joke, but there’s some truth there. This is my thank you to the craft, and to the people who helped me along the way, and maybe a toolkit for those coming after me.

—

The author of 8 novels and 2 short story collections, Richard Dansky is widely regarded as a leading expert on video game narrative and writing. He has written for franchises including The Division, Assassins Creed, Far Cry, Splinter Cell, and many others, and was also a key contributor to White Wolf’s classic World of Darkness horror RPG setting. His upcoming projects include the novel Nightmare Logic from Falstaff Dread, the graphic novel Bridgewater from Delcourt, and the nonfiction book The Video Game Writer’s Guide To Surviving an Industry That Hates You. He also likes scotch.